Tracheoesophageal Fistula Surgery in Mumbai

A tracheoesophageal fistula is a serious but treatable condition in which an abnormal channel forms between the trachea (windpipe) and the oesophagus (food‑pipe) When identified promptly and managed by a specialised team. With advances in thoracic surgery, many patients achieve good long‑term outcomes. If you suspect TEF or have been diagnosed and are seeking expert surgical care, Dr. George provides consultation and treatment for thoracic airway and oesophageal disorders.

What is a Tracheoesophageal Fistula?

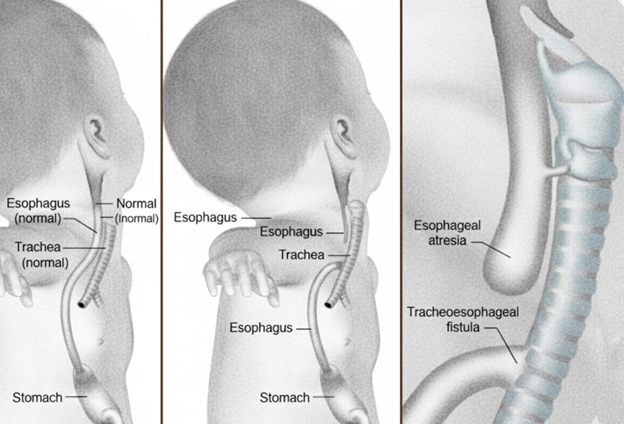

In a healthy individual, the trachea and oesophagus are two separate tubes: the trachea carries air to and from the lungs; the oesophagus carries food and liquids to the stomach. In TEF, an abnormal connection develops between these two tubes, allowing food, liquids or secretions to pass into the airway and lungs, or air to pass into the oesophagus. This abnormal communication can compromise both breathing and swallowing and predispose to serious complications.

TEF may be present from birth (congenital) or may develop (acquired) later due to injury, surgery, prolonged mechanical ventilation, infection or malignancy.

Types and Classification of TEF

The condition is broadly classified into two categories:

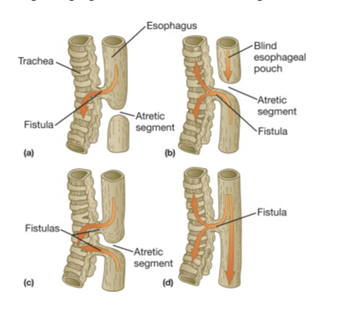

Congenital TEF

This form arises during fetal development, when the trachea and oesophagus fail to separate properly. Several anatomical patterns exist; for example, the classic form combines oesophageal atresia (blind‐ended oesophagus) with a distal fistula.

“Esophageal atresia with distal TEF” accounts for about 87 % of cases.

Other types include isolated TEF without oesophageal atresia (so‑called H‑type).

Acquired TEF

This form occurs after birth, and may be due to prolonged intubation/tracheostomy, surgery in the chest/neck region, mediastinal infection, penetrating trauma or tumour‑related erosion.

The anatomical location may vary—near the carina, in the main bronchus region or at other levels of the airway.

Signs and Symptoms to Watch For

In infants (congenital TEF):

● Feeding difficulty, choking or coughing during feeds

● Excessive salivation or drooling

● Episodes of cyanosis (turning blue) when trying to feed

● Pneumonia soon after birth

● Difficulty passing a nasogastric tube into the stomach (in the case of oesophageal atresia)

In older children or adults (acquired TEF):

● Persistent cough or coughing when swallowing liquids

● Recurrent lung infections or aspiration pneumonia

● Air in the stomach or oesophagus when breathing (rare)

● Sudden onset of respiratory distress in a patient with prior chest surgery or prolonged ventilation

Because the symptoms may be subtle or mistaken for other airway/oesophageal disorders, a high index of suspicion is needed especially in patients with risk factors.

How is TEF Diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves a combination of clinical suspicion, imaging and endoscopic evaluation:

● Contrast swallow study of the oesophagus may show leakage into the airway or filling of trachea by oesophageal contrast.

● Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may delineate the anatomy of the fistula, its size and relationship to the trachea/oesophagus.

● Bronchoscopy (with airway endoscopy) and oesophagoscopy allow direct visualisation of the fistulous opening.

● Nutritional and respiratory status assessment is essential before planning definitive management.

Surgical & Non‑Surgical Treatment Options

Initial considerations:

In both congenital and acquired cases, optimising the patient beforehand is important: control of infection, nutritional support, and ventilatory weaning if possible.

Surgical repair:

● In congenital TEF the standard approach is early surgical closure of the fistula and repair of the oesophagus (and sometimes the trachea) shortly after birth.

● In acquired TEF the surgery may involve division of the fistulous tract, closure of the oesophageal defect, tracheal repair (or resection/anastomosis if stenosis is present), and often interposition of vascularised muscle/flap between oesophagus and trachea to prevent recurrence.

● Surgical approach may vary: cervical collar incision, sternotomy, thoracotomy, depending on location.

● Advanced techniques: in certain cases minimally invasive (thoracoscopic) or endoscopic management may be considered.

Post‑operative care and follow‑up:

● The patient will often need airway and feeding support in the early period.

● Monitoring for leaks, airway stenosis, recurrent fistula, swallowing dysfunction, and growth (in children) is critical.

● Long‑term follow‑up for respiratory complications, gastro‑oesophageal reflux (which may compromise the repair) is important.

Living With or After TEF – What Patients/Parents Should Know

After repair, patients (or parents of infants) should focus on:

● Regular follow‑up with both thoracic surgery and appropriate allied teams (nutritionist, physiotherapy, speech/swallowing therapy)

● Monitoring growth (in children), nutritional adequacy, and respiratory health

● Avoiding choking episodes, aspiration—especially when feeding new textures

● Promptly addressing respiratory symptoms (wheezing, cough, recurrent infections)

● Recognising signs of narrowing (dysphagia, vomiting) or reflux (heartburn, regurgitation)

● In adult/ acquired TEF cases, ensuring the underlying cause (e.g., malignancy) is also addressed.

When Should You Consult a Thoracic Surgeon?

If you or your child has symptoms such as persistent coughing during feeds, recurrent pneumonia, aspiration, or if a fistula between the airway and food‑pipe is suspected or diagnosed, it is advisable to consult a thoracic surgical specialist. An assessment will typically involve imaging, endoscopy and a personalised treatment plan. Early referral is advantageous in achieving the best outcome.

Frequently Asked Questions

In congenital cases, the cause is abnormal embryological separation of the trachea and oesophagus. In acquired cases, causes include prolonged intubation/tracheostomy, chest surgery, trauma, infection or tumour erosion.

Most infants undergo early surgical correction whereby the fistula is closed and the oesophagus repaired (often in the neonatal period). Good outcomes depend on early diagnosis, absence of major associated anomalies and skilled surgical care.

Yes — though rare, TEF can occur in adults (acquired form) due to prolonged ventilation, tracheostomy, mediastinal infection, or tumour erosion.

Yes — because the abnormal connection between airway and oesophagus poses a high risk of aspiration, pneumonia and respiratory compromise. Surgery to close the fistula and repair the oesophagus/trachea is the standard of care.

Non‐surgical measures (nutritional support, managing aspiration, stenting) may be used temporarily or when surgery is not immediately feasible; however definitive closure of the fistula by surgery remains the treatment of choice. Newer techniques (e.g., occluder devices) are emerging in selected cases (especially malignant TEF) but are not standard yet.